On the Political and Ethnic History of Myrzakan (Samurzakano) in the 19th Century, By Denis Gopia

Аҧсуаҭҵаара / Abkhaz Studies. No.12. Sukhum. 2022. pp. 99-111

Academy of Sciences of Abkhazia

Abkhaz Institute of Humanitarian Research Named after D.I. Gulia, AbIGI 2022

Аҧсуаҭҵаара / Abkhaz Studies. No.12. Sukhum. 2022. pp. 99-111

The article is also available in PDF format in both Russian (original) and English.

Throughout different historical periods, any state undergoes complex political processes, including the expansion and contraction of political and ethnic boundaries. Abkhazia, one of the oldest states in the Caucasus, is no exception to this rule. Following the events of the Russo-Caucasian War in the 19th century, Abkhazia became a multi-ethnic country. Its land was colonised by Russians, Armenians, Estonians, etc., while the eastern part of the country, namely the modern Gal District, was ethnically populated by Megrelians and Georgians. The Gal District of Abkhazia is located in the southeast of the country, covers an area of 500 sq. km., borders the Ochamchira District of Abkhazia to the west, the Tkuarchal District to the north, and to the east along the Ingur River - with the Samegrelo and Upper Svaneti regions of the Republic of Georgia, with the city of Gal as its administrative centre.

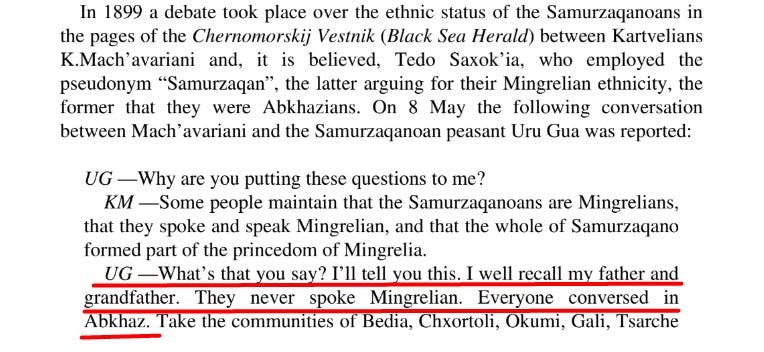

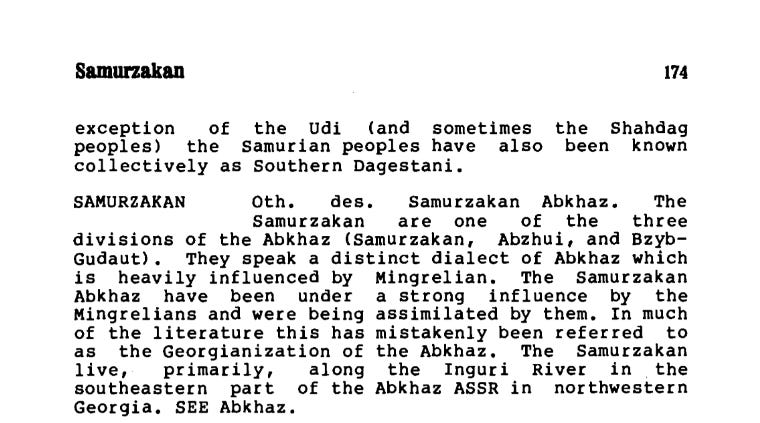

In the past, this region of Abkhazia was called Myrzakan (Samurzakano in Russian sources. Note by Gopia D.K.), but it is this region of Abkhazia that has caused and continues to cause many disputes about its historical affiliation to either Abkhazia or Georgia. In its historical past, this region was part of the ancient Abkhazian kingdom of Apsilia (1st-7th centuries), inhabited by one of the ancient Abkhazian tribes. From the 8th to the 13th centuries, it was part of the Kingdom of Abkhazia, but by the end of the 13th and the beginning of the 14th century, it was annexed by Giorgi Dadiani to the Principality of Megrelia and underwent partial Megrelisation.

At the end of the 17th century, as a result of a prolonged struggle, the reconquest of this territory was completed, and the ruling dynasty of Abkhazia, the Chachbas (Shervashidzes), reclaimed their region.

Further reading and quotes from different sources

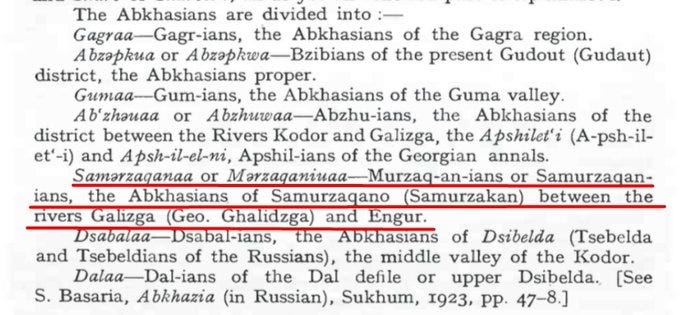

+ Samurzakanians or Murzakanians by Simon Basaria

+ Excursion to Samurzakan and Abkhazia [Excursion au Samourzakan et en Abkasie], by Carla Serena

+ Challenging Georgian Narratives (Response 2): A Further Exploration on Abkhazia by Stanislav Lakoba

+ Who are the Mingrelians? Language, Identity and Politics in Western Georgia, by Laurence Broers

In the political sense, the Mingrelians are just as Russian as the Muscovites, and in the same direction they can influence every tribe in contact with them, a striking proof of which is the fact, recognised by our opponent, that due to the influence of the Mingrelians, the Samurzaqanoans are a branch of the Abkhazian tribe, – being in constant communication with the Mingrelians, they became completely Russian subjects and during the repeated uprisings of their fellow tribesmen did their best to help the government in suppressing disturbances and pacifying the rebels.

― Jakob Gogebashvili (Who should be settled in Abkhazia?, Tiflisky Vestnik, 1877)

Translation:

In the previous letter, we tried to show what Sukhum was and what it has become; now let us say a few words about the former and present situation of Abkhazia in general.

Before the war, the Sukhum District consisted of four sections: Gudauta, Gumista, Kodori, and Samurzakan, of which the first two formed the Pitsunda District, whilst the latter two formed the Ochamchira District. The total population of the Districts amounted to 80 thousand souls, almost evenly distributed among the Districts.

The Abkhazians proper (the Apswa) inhabited the first three regions: the population of Samurzakan, although undoubtedly belonging to the same tribe, was influenced by proximity to, and kinship-ties with, the population of Mingrelia in its language and customs to such an extent that it formed, so to say, a separate tribe.

The similarity of the Samurzakans with the Abkhazians was preserved in the class-rights, in the relations of the higher classes to the lower ones, in some folk-customs that have passed down to the present generation from their common ancestors, and in the identity and kinship of the Tavad and Aamsta (princely and noble) families. The language of the Samurzakans is not considered to be the pure Abkhazian language, but, being a mixture of the latter and Mingrelian, it is called the Samurzakan dialect.

The conscientious forces of Samurzakan, with the exception of one or two renegades, ‘lads’ of the Tiflis ministers, expressed clear lack of sympathy for all this. All of them said that the Samurzakanians were Abkhazians, and therefore they found their territorial and cultural rejection from the whole of Abkhazia to be the greatest injustice; everywhere they protested, pointing out the madness of the Tiflis chauvinists, who were excessively carried away by foul national[istic] aspirations and were therefore going against the elementary rights of the Abkhazian nation.

Such enlightened Samurzakanians as the engineer Kakuba, the barrister Zukhbaja, the learned forestry specialist Gamisoni, Dr. V. Achba, E. Eshba, N. Akirtava and many male and female students did not absolutely share the policy of the aggressors in relation to Samurzakan.