Dolmens and Cromlechs in the Western Caucasus: An Overview

This article gives an overview of the ancient dolmens and cromlechs of the Western Caucasus, highlighting their significance in Bronze Age burial rituals and regional history.

The Western Caucasus, a region rich in ancient history, is home to a fascinating array of megalithic structures, including dolmens and cromlechs. These monuments, often associated with burial practices and rituals, have long intrigued archaeologists due to their distinctive architectural styles and mysterious purposes. Scattered throughout the verdant landscapes of Abkhazia and the broader Western Caucasus, these dolmens represent some of the earliest examples of monumental stone architecture, dating back to the Bronze Age (3250–1250 BC). Their significance in the cultural and religious life of the region continues to be a subject of study, offering insights into the societies that constructed them.

Dolmens and Cromlechs - Architectural Marvels of the Bronze Age

Dolmens were not unique to the Caucasus; they were widespread across Asia, Africa, and Europe. Archaeologists suggest that the concept of building these structures likely spread via maritime routes, following a 'relay' model of transmission. This global context highlights the significance of the Western Caucasian dolmens as part of a broader megalithic tradition.

Dolmens, derived from the Celtic tol-men meaning ‘stone table’, are among the oldest architectural relics of Abkhazia. Constructed during the Middle Bronze Age (late 3rd to 2nd millennium BC), they were primarily used as monumental tombs. Abkhazia houses about eighty of these dolmens, with notable examples found in Eshera, Azanta, Otkhara, and Mikalripsh.

The dolmens in Abkhazia can be categorised into slab-built and trough-shaped types. The slab-built dolmens, commonly seen in areas like Eshera and Azanta, consist of six large slabs of limestone or sandstone, forming the four walls, the roof, and the floor. A distinctive feature of these dolmens is the presence of a hole in the front slab, which allowed for the insertion of human remains. This opening was sealed with a heavy stone plug, isolating the deceased from the living, which archaeologists believe may have had symbolic or spiritual significance. The careful attention given to sealing the tombs suggests a deep concern for protecting the spirits of the dead.

Trough-shaped dolmens, found in locations such as Gudauta and Ochamchira, are also notable for their construction. These dolmens are slightly different in form, with the main chamber resembling a large stone trough, often without a visible access hole. The stones used in these structures were meticulously fitted together, indicating a high degree of architectural skill and effort. Some of the larger dolmens, such as those in Eshera, measure up to 5.25 by 4.85 metres, with slabs weighing as much as 22.5 tonnes. These impressive dimensions highlight the labour and organisation involved in their construction, suggesting a significant cultural or ritualistic importance.

It is significant to note that dolmens are not found in other regions of the Caucasus, such as Chechnya, Dagestan, Ossetia, or Georgia (including Mingrelia and Svanetia). While isolated megaliths exist in these areas, they bear no typological or external resemblance to the dolmens of the Western Caucasus. This distinct distribution sharply separates the Western Caucasus from the rest of the Caucasus in terms of megalithic culture.

Cromlechs, from the Celtic cromlech meaning "round place," consist of large stones arranged in concentric circles. These formations are thought to have been associated with ancestor worship and were sites for secondary burials, where only select bones or items belonging to the deceased were interred. The concentration of cromlechs in areas such as Gagra and Gulripsh points to the region’s cultural diversity in burial practices during the Bronze Age.

Group burials were often conducted at the centre of the cromlechs. While the Western Caucasian cromlechs were smaller in scale, it's worth noting that the largest cromlech in the world, Stonehenge in England, served as a temple dedicated to the sun.

The construction of dolmens can be placed within the context of the region’s broader architectural history. These megalithic structures predate the arrival of Greek colonists on the Abkhazian coast, yet they laid the groundwork for monumental stone architecture that would flourish during the Hellenistic period. The attention to stone masonry in dolmen construction, with stones carefully worked to create airtight seals, demonstrates a continuity of stone-building traditions that later evolved into Greek defensive walls and public buildings.

The widespread practice of secondary burials in dolmens, where skulls and other bones were placed long after death, indicates that these structures had long-term ritual significance. Items found in these tombs, including clay vessels, bronze hooks, and daggers, suggest that the dolmens served as more than just burial sites; they were also places of offering and remembrance.

Distribution and Diversity of Dolmens Across the Western Caucasus

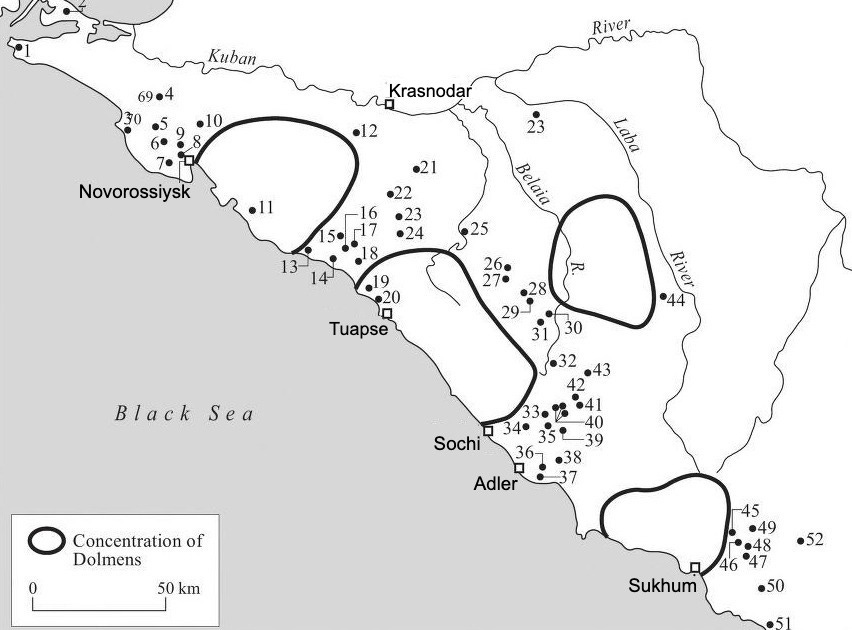

The broader Western Caucasus boasts a dense concentration of dolmens, making it one of the most significant areas for studying megalithic structures. Over 3,000 dolmens once dotted the verdant slopes of this region, of which archaeologists have excavated only about 160 to date. These structures are typically found between 250 and 400 metres above sea level, with a few situated above 1,000 metres. The most significant clusters are located near Kizinka village and Bagovskaya in Krasnodar Krai.

Dolmens in the Western Caucasus exhibit a range of forms, from simple plinth types to more complex composite and monolithic variants. The plinth dolmens, accounting for the majority, are typically rectangular or trapezoidal in shape, with well-fitted stone slabs forming the walls and roof. These dolmens, though simple in appearance, required significant engineering skill to transport and position the massive stones used in their construction. Some dolmens have a circular or polygonal plan, reflecting a variety in local architectural traditions. The construction methods employed in these dolmens, particularly the use of tongue-and-groove joints, show the builders’ advanced craftsmanship and understanding of stone-working techniques.

Some dolmens in the Western Caucasus, particularly those near the Black Sea coast, are adorned with unique decorative elements. Carved anthropomorphic stick figures and animal images have been found on the walls of dolmens, such as those at the Dzhubga site. These carvings, though simple, provide rare insights into the artistic expressions and possibly the belief systems of the dolmen builders. Additionally, some dolmens feature cup-shaped hollows on their capstones, the purpose of which remains a subject of debate among archaeologists.

Advanced field techniques have revolutionised our understanding of some dolmen sites. For instance, the Dzhubga dolmen, long considered a free-standing structure, was revealed in 2006 to be part of a much more complex monument. New excavations uncovered a circular courtyard defined by a 2.5-meter-high sandstone wall, demonstrating that what was once thought to be a simple tomb was actually an elaborate ritual complex covering an area of about 700 square metres. Such discoveries highlight the potential for future research to dramatically alter our perception of these ancient structures.

The distribution of dolmens is also noteworthy. While Abkhazia contains many isolated examples, the broader region features large clusters, with some areas hosting hundreds of dolmens. The largest known group, near Bagovskaya, consists of over 500 dolmens, spread across several kilometres. This dense concentration suggests that the Western Caucasus was a major cultural and ritual centre during the Bronze Age. The extensive use of stone in these monuments, as well as their strategic placement along important routes, points to the significance of these sites in the social and religious life of the time.

Cultural Significance and Modern Interpretations

The exact purpose of the dolmens remains a topic of debate among archaeologists. Theories about their purpose range from ancestral veneration to territorial markers or symbols of social hierarchy. Most scholars agree that they served as burial sites, but there is also evidence to suggest that they may have had other functions. The presence of offerings, such as food and bronze artefacts, indicates that these structures were also used in ritual activities, possibly related to ancestor worship or territorial marking. Some scholars have suggested that the placement of dolmens along trade routes or near important natural landmarks may indicate their role in the broader socio-economic networks of the time.

The origins of dolmen building in the Western Caucasus remain a subject of scholarly debate. Some researchers draw parallels with megalithic traditions stretching from Western Europe to India, suggesting possible cultural diffusion or shared ancestral practices. Others argue for an independent development, pointing to the unique characteristics of Caucasian dolmens. The abrupt appearance of these structures in the region, seemingly unconnected with earlier local traditions, has fueled various theories about their origins, including notions of maritime or terrestrial migrations. However, the consensus among modern scholars is that these dolmens represent a local response to broader cultural influences, adapted to the specific geographical and social conditions of the Western Caucasus.

Soviet archaeologists, particularly Vladimir Ivanovich Markovin (1922–2008), developed detailed classificatory schemes for these burial chambers. These schemes were based on the mode of construction (whether single or multiple slabs of stone), the dimensions of basic elements such as the porch and rooms, and the nature of features like access holes. While somewhat outdated now, these classifications provided a foundation for understanding the variety and complexity of dolmen structures in the region.

One theory posits that the dolmens acted as markers of social status, with the larger and more elaborate structures reserved for high-ranking individuals. The inclusion of grave goods, such as weapons and jewellery, supports the idea that these monuments were built for elites, who were honoured in death with grandiose tombs.

The construction of these dolmens, often requiring the transportation of large stone slabs over considerable distances, would have demanded a high degree of social organisation. This, in turn, suggests that the societies of the Western Caucasus during the Bronze Age were complex and stratified, capable of mobilising resources and labour for large-scale construction projects. The presence of grave goods, such as bronze weapons and ornaments, further points to the existence of a warrior elite, with the dolmens serving as monumental tombs for high-status individuals.

The dolmens of the Western Caucasus were more than just burial sites; they were places of worship and ritual. The practice of dolmen worship in the region is well-documented, with records suggesting that it persisted into the 19th century. Leonid L. Lavrov (1909–1982) observed that Circassians, particularly the Shapshughs, left sacrificial food near the entrances of dolmens as offerings. This suggests that these sites were not merely graves but continued to serve as important spiritual centres for local communities.

Shalva D. Inal-Ipa noted that the Abkhazians also venerated these ancient monuments. He describes how the dolmens were integrated into the local religious landscape, becoming places of pilgrimage and worship. Even today, many dolmen sites attract visitors, who come not only to admire the architecture but also to engage in acts of remembrance and reverence.

The distribution of dolmens provides intriguing insights into the ethno-genesis of the region. By examining the maps of dolmen distribution created by Vladimir Markovin, Leonid Lavrov, and Shalva Inal-Ipa (1916–1995), it becomes evident that the dolmen culture densely covered the territories of the Western Caucasus historically linked to the Abkhaz-Circassian peoples. This territory likely played a critical, perhaps the most important, role in the ethno-genesis of the Abkhaz-Circassian people. While this process may have occasionally been interrupted in the Trans-Kuban plains (also known as the Prikuban inclined plain, located in Krasnodar Krai and the Republic of Adygea) and more frequently in Southern Abkhazia or the Central Pre-Caucasus, it appears to have been continuous throughout history.

Dolmens and cromlechs in the Western Caucasus offer a fascinating glimpse into the prehistoric cultures of the region. These megalithic structures, whether serving as tombs, ritual sites, or territorial markers, were clearly significant to the societies that built them.

The study of these structures is crucial for understanding the social, cultural, and technological developments of the Bronze Age in the Caucasus. As researchers continue to uncover new evidence and refine existing theories, the dolmens of this region remain key to unlocking the mysteries of ancient Caucasian societies. Whether viewed as monuments to the dead, markers of social power, or symbols of cultural continuity, they stand as enduring testaments to the ingenuity and spirit of the people who built them thousands of years ago.

References

Agrbа, B.S. and Khotko, S.Kh., 2004. «Ostrovnаya» tsivilizаtsiya Cherkesii. Cherty istoriko-kul'turnoy sаmobytnosti strаny аdygov. Maykop: GURIPP "Adygeya".

Markovin, V.I., 2002. Western Caucasian Dolmens. Anthropology & Archeology of Eurasia, 41(4), pp.68-88.

Sagona, A., 2017. The Archaeology of the Caucasus: From Earliest Settlements to the Iron Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Trifonov, V.A., Zaitseva, G.I., van der Plicht, J., Kraineva, A.A., Sementsov, A.A., Kazarnitsky, A., Burova, N.D. and Rishko, S.A., 2014. Shepsi, the Oldest Dolmen with Port-Hole Slab in the Western Caucasus. Radiocarbon, 56(2), pp.1-10.

Trifonov, V.A., 1987. Nekotorye voprosy prednenazhatskikh sviazei maikopskoi kul'tury. Kratkie Soobshcheniia Instituta Arkheologii, 192, pp.18-26.

Trifonov, V.A., Zaitseva, G.I., van der Plicht, J., Burova, N.D., Bogomolov, E.S., Sementsov, A.A. and Lokhova, O.V., 2012. The Dolmen Kolikho, Western Caucasus: Isotopic Investigation of Funeral Practice and Human Mobility. Radiocarbon, 54(3-4), pp.761-769.

Voronov, Y.N., 1978. V mire аrkhitekturnykh pаmyatnikov Аbkhаzii. Moscow: Iskusstvo.

Further Reading

Bartsyts, R.M., 2010. Аbkhаzskiy religioznyy sinkretizm v kul'tovykh kompleksаkh i sovremennoy obryadovoy prаktike. Sukhum.

Lavrov, L.I., 1978. Istoriko-etnogrаficheskie ocherki Kаvkаzа. Leningrad: Nauka.

Markovin, V.I., 1978. Dol'meny Zаpаdnogo Kаvkаzа. Moscow: Nauka.

Markovin, V.I., 2008. Cüce Evleri İspunlar: Kuzeybatı Kafkasya Dolmenleri. Translated by O. Uravelli. Ankara: KAFDAV Yayınları.

Sharikov, Y.N. and Komissar, O.N., 2011. Dolmeny Kаvkаzа: Geologicheskie аspekty i tekhnologiya stroitel'stvа. Krasnodar.

Trifonov, V.A., 1983. Steppe Kuban region in the early and middle bronze age: Periodization and cultural-historical characteristics. Ph.D. Institute of Archaeology, Leningrad.

Voronov, Y.N., 2006. Nаuchnye trudy v semi tomаkh, Tom pervyy. Sukhum: Abkhazian Institute of Humanitarian Research ANA.

Voronov, Y.N., 1982. Drevnosti Аzаntskoy doliny. Tbilisi: Metsniereba.